Uterine fibroids are noncancerous growths of the uterus that often appear during childbearing years. Also called leiomyomas (lie-o-my-O-Muhs) or myomas, uterine fibroids aren't associated with an increased risk of uterine cancer and almost never develop into cancer.

Fibroids range in size from seedlings, undetectable by the human eye, too bulky masses that can distort and enlarge the uterus. You can have a single fibroid or multiple ones. In extreme cases, multiple fibroids can expand the uterus so much that it reaches the rib cage.

Many women have uterine fibroids sometime during their lives. But most women don't know they have uterine fibroids because they often cause no symptoms. Your doctor may discover fibroids incidentally during a pelvic exam or prenatal ultrasound.

Many women who have fibroids don't have any symptoms. In those that do, symptoms can be influenced by the location, size, and a number of fibroids. In women who have symptoms, the most common symptoms of uterine fibroids include:

Rarely, a fibroid can cause acute pain when it outgrows its blood supply and begins to die.

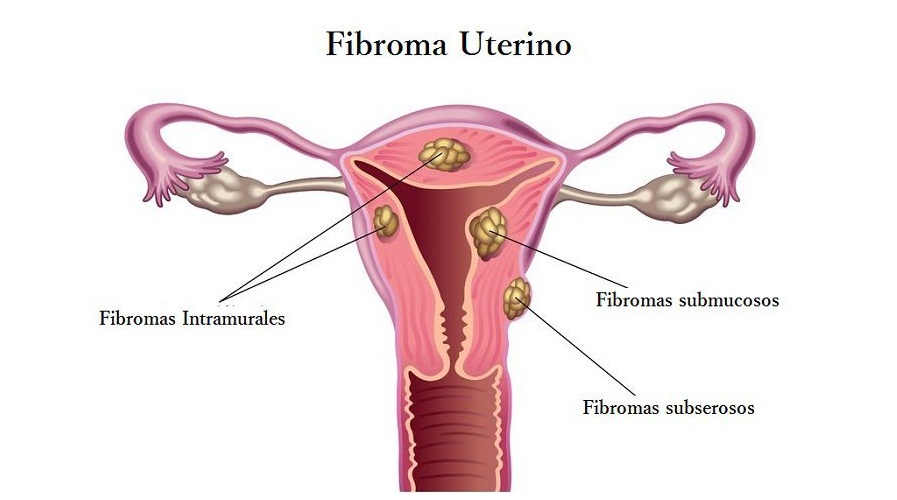

Fibroids are generally classified by their location. Intramural fibroids grow within the muscular uterine wall. Submucosal fibroids bulge into the uterine cavity. Subserosal fibroids project to the outside of the uterus.

Doctors don't know the cause of uterine fibroids, but research and clinical experience point to these factors:

Doctors believe that uterine fibroids develop from a stem cell in the smooth muscular tissue of the uterus (myometrium). A single cell divides repeatedly, eventually creating a firm, rubbery mass distinct from nearby tissue.

The growth patterns of uterine fibroids vary — they may grow slowly or rapidly, or they may remain the same size. Some fibroids go through growth spurts, and some may shrink on their own. Many fibroids that have been present during pregnancy shrink or disappear after pregnancy, as the uterus goes back to a normal size.

Fibroids are almost always benign (not cancerous). Rarely (less than one in 1,000) a cancerous fibroid will occur. This is called leiomyosarcoma. Doctors think that these cancers do not arise from an already-existing fibroid. Having fibroids does not increase the risk of developing a cancerous fibroid. Having fibroids also does not increase a woman's chances of getting other forms of cancer in the uterus.

Asymptomatic small or medium-sized fibroids alone are unlikely to present the significant risk to pregnancy. However, fibroids may increase in size as a result of increased levels of hormones and blood flow to the uterus during pregnancy. The growth of fibroids may cause discomfort, feelings of pressure, or pain. Additionally, large or multiple fibroids can increase the risk of:

Cesarean section The risk of needing a c-section is six times greater for women with fibroids. Breech Presentation- The baby is positioned with its legs down and head up rather than the head down.

Placental abruption The placenta breaks away from the wall of the uterus before delivery. When this happens, the fetus may not receive oxygen.

Preterm delivery Talk to your obstetrician if you have fibroids and become pregnant. All obstetricians have experience dealing with fibroids and pregnancy. Most women who have fibroids and become pregnant do not need to see an OB who deals with high-risk pregnancies.

Although this treatment may be successful in destroying the fibroids causing painful symptoms, at a later time, more fibroids may grow, become symptomatic and require additional treatment. This is true for all fibroid treatments, except hysterectomy where the entire uterus is removed.

Your doctor may find that you have fibroids when you see her or him for a regular pelvic exam to check your uterus, ovaries, and vagina and for an annual cervical PAP smear. The doctor may be able to feel the fibroid with his or her hands during an ordinary pelvic exam, as a (usually painless) firm lump on the uterus. For medium and larger fibroids, your doctor will describe the size of your fibroids by comparing them to different stages of pregnancy. For example, you may be told that the size of your fibroids is similar in size to a uterus carrying a 20-week pregnancy (at the level of the belly button). Or the fibroid might be compared to fruit such as lemons, oranges or grapefruit to demonstrate a comparative size. One of several imaging tests generally confirms the size, position, and dynamic of Fibroids. The two most common modalities include Ultrasound and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

There are various factors that can increase a woman's risk of developing fibroids.

Age. Fibroids become more common as women age, especially during the 30s and 40s through menopause. After menopause, fibroids usually shrink.

Family history. Having a family member with fibroids increases your risk. If a woman's mother had fibroids, her risk of having them is about three times higher than average.

Ethnic origin. African-American women are more likely to develop fibroids than white women.

Obesity. Women who are overweight are at higher risk for fibroids. For very heavy women, the risk is two to three times greater than average.

Eating habits. Eating a lot of red meat (e.g., beef) and ham is linked with a higher risk of fibroids. Eating plenty of green vegetables seems to protect women from developing fibroids.

The Acessa device is a new FDA approved surgical procedure that aims to effectively treat fibroids with a minimally invasive outpatient procedure. Acessa uses radiofrequency energy to heat fibroid tissue and cause instantaneous cell death. The necrotic cells are then reabsorbed by the lymphatic system resulting in decreased fibroid size and improved symptoms. The Acessa device is placed within the fibroid under ultrasound guidance during a standard outpatient pelvic laparoscopy.

In the pivotal trial for FDA approval of 135 women, fibroid symptoms decreased by 52% and fibroid volume decreased an average of 40% within 3 months of treatment. These therapeutic effects were persistent through 12 months of follow-up with 56% decrease in symptoms and 45% decrease in fibroid volume from pre-procedure values. Sixty one percent of study participants were very satisfied with treatment and 80% reported they would definitely recommend the treatment to a friend. The Acessa procedure resulted in minimal blood loss and an average return to normal activities of 9 days.