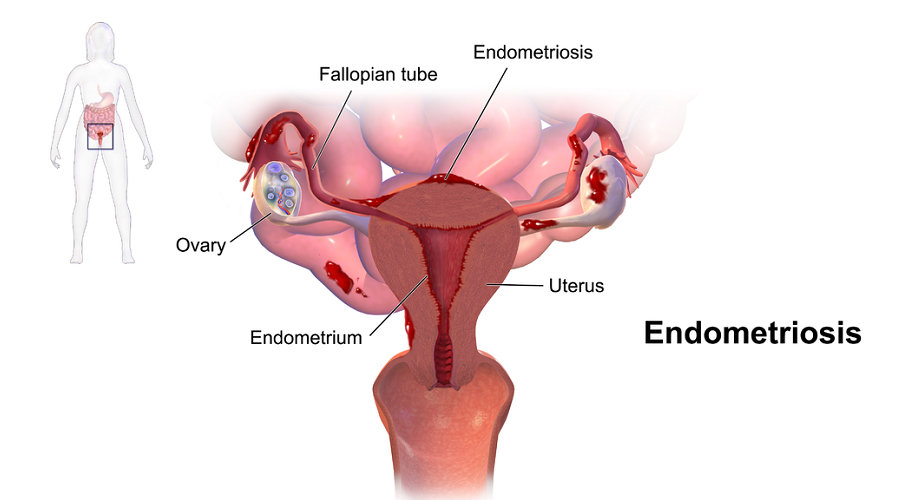

Endometriosis (en-doe-me-tree-O-sis) is an often painful disorder in which tissue that normally lines the inside of your uterus — the endometrium — grows outside your uterus. Endometriosis most commonly involves your ovaries, fallopian tubes and the tissue lining your pelvis. Rarely, endometrial tissue may spread beyond pelvic organs.

With endometriosis, displaced endometrial tissue continues to act as it normally would — it thickens, breaks down and bleeds with each menstrual cycle. Because this displaced tissue has no way to exit your body, it becomes trapped. When endometriosis involves the ovaries, cysts called endometriomas may form. Surrounding tissue can become irritated, eventually developing scar tissue and adhesions — abnormal bands of fibrous tissue that can cause pelvic tissues and organs to stick to each other.

Endometriosis can cause pain — sometimes severe — especially during your period. Fertility problems also may develop. Fortunately, effective treatments are available.

The primary symptom of endometriosis is pelvic pain, often associated with your menstrual period. Although many women experience cramping during their menstrual period, women with endometriosis typically describe the menstrual pain that's far worse than usual. They also tend to report that the pain increases over time.

Common signs and symptoms of endometriosis may include:

The severity of your pain isn't necessarily a reliable indicator of the extent of the condition. Some women with mild endometriosis have intense pain, while others with advanced endometriosis may have little pain or even no pain at all.

Endometriosis is sometimes mistaken for other conditions that can cause pelvic pain, such as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) or ovarian cysts. It may be confused with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a condition that causes bouts of diarrhea, constipation and abdominal cramping. IBS can accompany endometriosis, which can complicate the diagnosis.

Although the exact cause of endometriosis is not certain, possible explanations include:

Several factors place you at greater risk of developing endometriosis, such as:

Endometriosis usually develops several years after the onset of menstruation (menarche). Signs and symptoms of endometriosis end temporarily with pregnancy and end permanently with menopause unless you're taking estrogen.

Beyond the pain mentioned above, the endometrial implants (or the “bits and pieces” of tissue from the endometrium that have attached somewhere in the pelvis) release chemical factors that cause a toxic environment in the pelvis, making it harder for people to conceive, according to Nelson. “We think it might impact how well eggs and sperm can recognize and interact with one another appropriately to fertilize and form an embryo,” he says. Also, in more severe cases of endometriosis, inflammation and scar tissue can develop. “If you have a lot of scar tissue, when a woman releases an egg to ovulate, the egg has a hard time finding its way around the scar tissue to be picked up by the Fallopian tubes,” Nelson adds. “Mechanically, if there’s a lot of scar tissue, it makes it hard to get pregnant.”

The easiest way to try and treat endometriosis-related pain—at least the less severe pain—is to take an anti-inflammatory, like ibuprofen, says Brasner. She recommends starting to take it a day or two before your period begins. Another option: hormonal contraceptives. “Hormonal contraceptives suppress ovulation,” she says. “Anything that helps suppress the action of the endometrium, since that tissue is so productive, is going to help.” The downside? The results don’t last forever. Many of them will reverse when you stop taking whatever medication you’re on, according to Brasner.

The absolute last resort would be to surgically remove your ovaries. But Brasner says that this is rarely done since it puts women into an immediate menopause, is completely irreversible, and will leave you biologically unable to have children for the rest of your life.

Though treatment depends on the severity of the endometriosis, Nelson says that the most effective (but not the only) way to try to get pregnant if you have the disease is via in vitro fertilization. That said, there is a less “aggressive” option to try prior to resorting to IVF: Taking medication that will help you grow more eggs, and then taking your husband’s sperm to try intrauterine insemination. If that doesn’t work after three or four attempts, IVF is the next step, says Nelson. Surgery to try to eliminate the endometriosis is also a possibility, though Nelson says that it doesn’t seem to improve things (from a fertility standpoint) as much as was previously thought. The bottom line: “Which of these is most appropriate depends upon you being evaluated by your physician, looking at the particulars, and making the decision,” says Nelson.

Going on birth control might be your best option. “There is a reason to consider suppression with birth control pills,” says Brasner. “We really believe birth control plays a role in keeping endometriosis from progressing. It’s not only for current symptom management, but for progression as well.”